Does scent have a gender? And who decides that?

X pour homme, Y pour femme: you can easily replace the X and Y with countless perfume brands that explicitly state on the bottle whether you are holding a perfume for women or for men. Other brands do it more subtly and choose a neutral name, but do have a category for women and a category for men on their website. Similarly, when you walk into a classic perfumery, you usually find a women's department and a men's department. At a time when gender identity has long ceased to be reducible to this binary division, this is remarkable. So who and what exactly determines whether a perfume is suitable for women or men?

It used to be about status, not gender

With the fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity, the culture of perfuming also disappears in Europe for several centuries. In the Middle Ages, people used perfume purely for medical and hygienic reasons. Indeed, they assume that bad smells can cause diseases.

The Crusades and trade with the East introduce the West to new and unknown products and fragrances. It creates a renewed interest in perfume that spreads further across Europe from Italy from the Renaissance onwards. Because it was thought that the plague (or black death) would enter your body through bathing in water, bathing is avoided. Perfume is used to cover up unpleasant odours. But because these raw materials are so expensive, only the rich nobility can afford them. The use of perfume therefore becomes not only an expression of 'cleanliness' but also an important status symbol. Gender distinctions are not made in the process. Louis XIV, for instance, liked to perfume himself with orange blossom.

With the rise of the middle class, new gender patterns emerge

It is only from the 19th Century onwards that certain stereotypes in perfume see the light of day in Europe. It is a time of economic growth, when a new middle class emerges who can gradually afford more luxury products. Thanks to industrial progress, it also becomes possible to produce these products faster and on a larger scale to meet this new demand. In the perfume industry, the discovery of synthetic ingredients in particular is driving tremendous growth.

But it is also a time when gender roles are starting to drift further apart. The middle-class man goes to the office, while the middle-class woman stays at home to look after the children and do the housework. Companies are cleverly capitalising on this, arbitrarily classifying their products according to those stereotypes. So too with perfume.

The perfume industry primarily targets women. Delicate floral fragrances are packaged in 'feminine', elegant and curved bottles and marketed with advertisements depicting a female ideal. Suddenly, perfume is no longer something for the 'rich', but of 'women'. It is a conscious strategy of those brands to reinforce social norms about how we should look and smell.

Successful men should no longer wear perfume. For them, from now on, a fresh aftershave and at most some cologne (invented in 1709 by Giovanni Maria Farina, who lived in Germany) or lavender water will suffice.

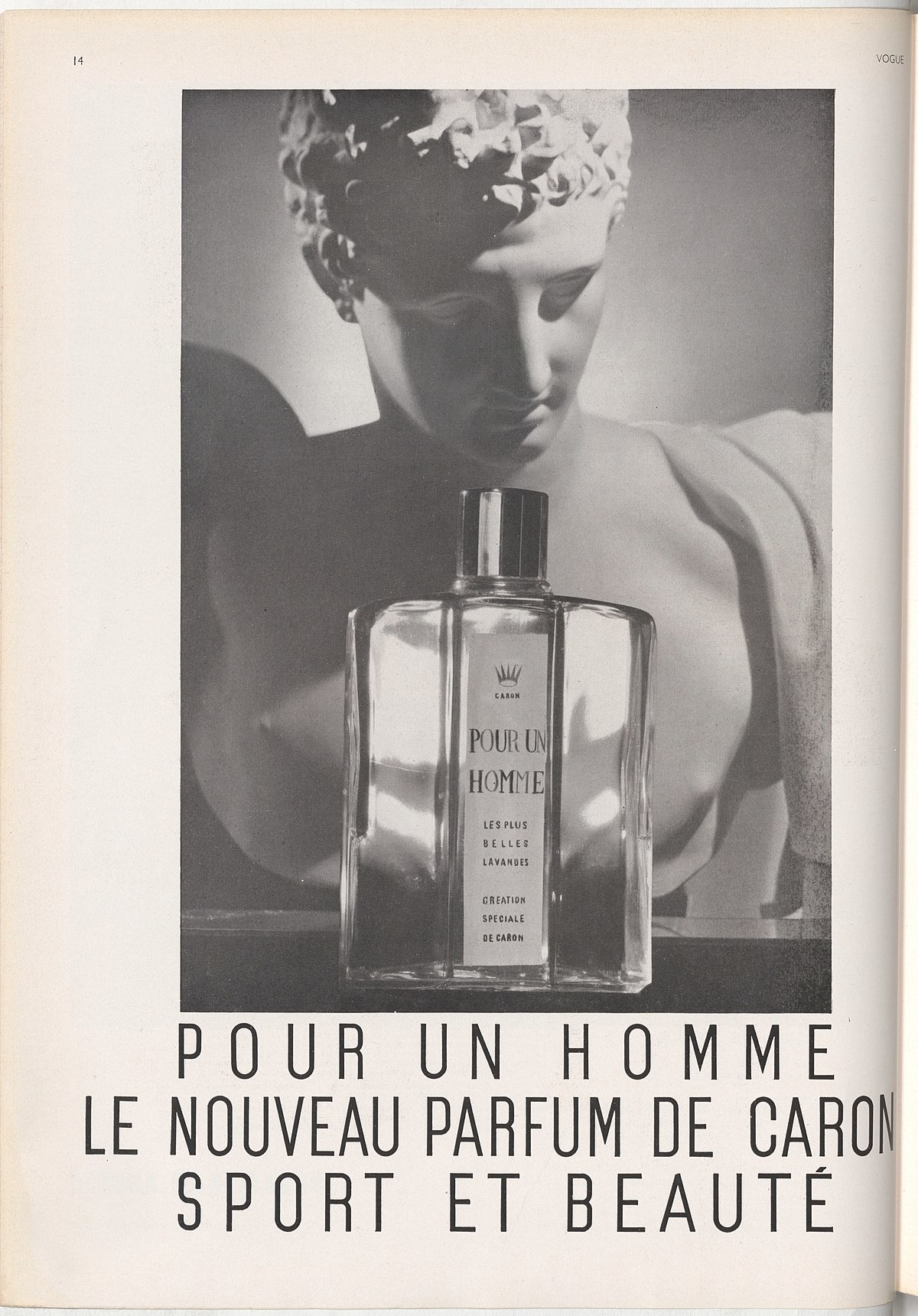

The rediscovery of men

In 1934, Caron creates the first 'men's perfume', an eau de toilette simply named "pour un homme". It becomes a huge hit, and is on sale to this day. The perfume industry suddenly discovers a new market. Brands that until then produced aftershave or focused mainly on women realise that change is imminent and start marketing perfumes for men. To convince men to use perfume again, they choose lighter versions: Eau de Cologne and Eau de Toilette. The term "perfume" is too strongly associated with women. The bottles exude virility, are angular and bold. The posters show successful men. The fragrances are aromatic and spicy.

Designer brands also smell money, and in turn launch men's fragrances. Pioneers Dior and Chanel were followed by other luxury brands in the 1970s, with fragrances such as Paco Rabanne pour homme (1973), Gucci pour homme (1976) and Ralph Lauren Polo (1978). The market boomed, and all brands rushed to avoid missing the boat. Most of these fragrances build on the success of Caron's first men's fragrance: they are all aromatic fougères with combinations of citrus, lavender, aromatic herbs, oakmoss and wood. Although some more variety comes later, with aquatic fragrances like Davidoff's Cool Water (1988) or Kenzo pour homme (1991).

Because of this persistent affirmation, people collectively start labelling floral and sweeter amber fragrances as 'feminine' and aromatic and wood fragrances as 'masculine'. These connotations, meanwhile, are deeply embedded in our memories. One generation 'learns' it from the previous and transfers it to the next.

Today, many brands still make that distinction between fragrances for men and for women, although there is a more diverse range in each segment. Many popular "men's fragrances" now include floral, fruit, sweet notes, amber and vanilla (think Le Male by Jean Paul Gaultier (1995), Amen by Thierry Mugler (1996) or more recently 1 Million by Paco Rabanne (2008)). But for fragrances labelled as very "feminine", the focus is still mainly on florals.

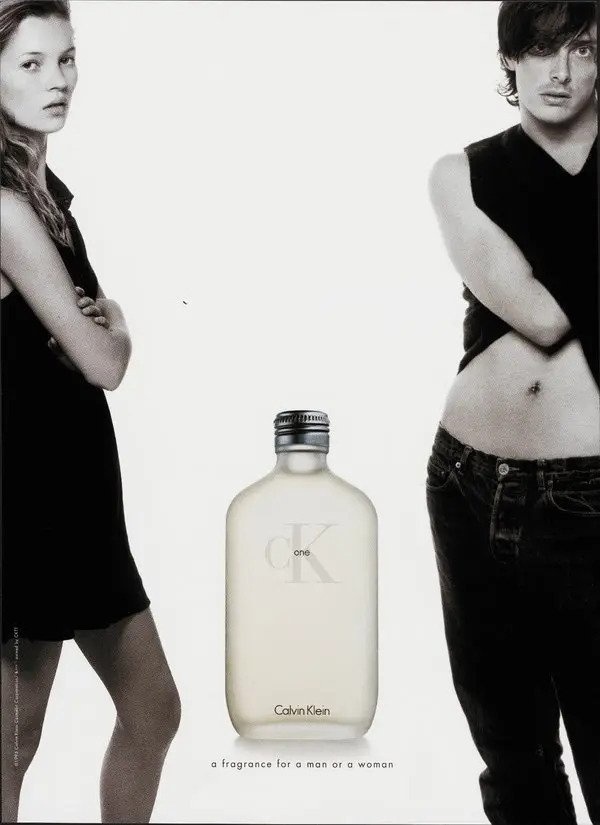

The first unisex fragrance

In 1994, Calvin Klein launched the first "unisex" perfume (CK One). It is an instant success, and other brands follow rapidly on this new trend. Suddenly you have three options: fragrances for men, for women and unisex fragrances. The latter smell rather fresh, sporty and neutral. They are not there to seduce. Was this a deliberate attempt to break gender roles in perfume, or a clever commercial move by someone who sensed the zeitgeist well?

Niche perfumes bring more freedom

The rise of niche perfumes in the 1980s, as a reaction to the marketing-dominated perfume industry where image and profit gradually took precedence over quality and originality, brings a new change. These brands go back to the basics, focusing on the quality of ingredients and the art of composition. They package their perfumes in uniform bottles, make no statement about 'gender' and rarely use models in their advertisements (if they advertise at all). For many people, to this day, it takes getting used to. They can no longer rely on that simple three-way division, but have to become familiar with notes, accords and fragrance families. It forces them to smell again and discover their own preferences, regardless of what marketing dictates.

Wear what you like, but test it first

150 years of stereotypes are firmly embedded in our collective 'scent memory', and still confirmed by quite a few brands. Although this artificial divide is mainly a Western phenomenon. In the Middle East, India and Maghreb countries, for instance, both men and women often wear the same floral, luscious perfumes, and in Brazil, lavender seems popular among women.

Nature does not distinguish whether a fragrance is masculine or feminine. Marketing has done that for decades. It is an entrenched cultural perception, which fortunately is increasingly being challenged. Perfume is there to provide pleasure and put you in a certain mood. It is an extension of your personality, not your gender or sex. So don't worry too much about it and just wear what you like. We do not offer any perfume that carries a gender label. If you look back at the history of perfume, you realise that this is simply an arbitrary classification made years ago by the perfume industry, at a time when gender patterns emerged that unfortunately still have not completely disappeared today.

The perfume industry is certainly not the most progressive industry, yet it does have an impact on perceptions in society. Not every perfume has to be 'unisex', because that too is a narrowing of reality. But it would be good if those simplistic divisions disappeared and perfumes simply became 'gender-free', where not a brand, but you yourself decide what you can and cannot wear. Even if that requires more effort and time to discover what suits you. And your gender can indeed affect how a perfume smells. The fragrance molecules in a perfume react differently on everyone's skin. Although everyone's skin chemistry is different, women tend to have more acidic skin than men. So a woman who finds a perfume "masculine" on her boyfriend may be surprised to find that the scent smells much more "feminine" when she wears it herself. Perfume does not have a gender, it gets the gender of who wears it. So testing on your skin before buying is the message.

First photo: Nicolas Comte on Unsplash